A continuous will to understand the other

At this year’s International Festival of Contemporary Theatre Homo Novus, artist duo Jānis Balodis (Latvia) and Nahuel Kano (Argentina), presented their work The Last Night of the Deer. It tells a story about a December night when Nahuel was traveling to Riga. Jānis picked him up from a ferry in Klaipeda. And, as they were driving, a severe snow storm started. They decided to take a smaller road where they accidently hit a deer. The performance inspired by Eduardo Kohn’s anthropology book How Forests Think tells a story about all-too-human forests and the more-than-human spirits that inhabit them, continuing the interest which permeates the works of both artists about the coexistence of different societies, individuals, phenomena and species, trying to answer the question – how are we here together? And are we together at all?

How was your show in Kuopio?

Jānis: I think it was good. It was a different space. But I think it went well together with the work. And also, leaving the city with the bus to travel to the location added to the experience of the performance in Kuopio.

Nahuel: The festival hired a bus and the audience was going like 15 minutes away from the city centre. This idea of traveling together added a lot. It was different from the performance in Riga.

What is your background? How did you two meet, what connected you?

Nahuel: Well, we met in Amsterdam, in the DAS Theatre master’s program in Amsterdam. We kind of clicked very quickly, because he had written to me: “Hey, can you help? I’m looking for an apartment.” And, we became close since then. We find it strange. For me, it was a surprise that there were a lot of connections between Latvia and Argentina. It was a good way of meeting beyond the personnel level or becoming friends and enjoying being together. So, from there, I think we started to also find points in common in terms of work and how we think about theatre, and also differences and that is the fun part.

Can you elaborate a little bit on these similarities and the connection points between Latvia and Argentina?

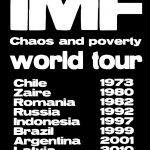

Jānis: I think, there are some, let’s say, an unfortunate fate that has happened or that the people went through – one of these things being the government organized violence and oppression against the people of the country. Argentina had a time of dictatorship and Latvia had a time of occupation. And, it is quite a wide topic – to think about its impact. But also, another way, I think, for me somehow even more important, was the, let’s say, the economical oppression from international organizations or the story of the practices of the International Monetary Fund. When we were working on the first work together at DAS, it was kind of an angry teenager’s room with posters on the walls, that kind of room I didn’t have at the time when I was a teenager. And there was one poster that looked like a poster rock bands create about their tour – a date and a city. But instead of a rock band being promoted, it was a poster for the International Monetary Fund, with a list of countries and the year the IMF “visited” the country. Argentina was in 2001, Latvia in 2010.

Nahuel: I think both countries are in a way peripheral, but also in the centre. Latvia is a peripheral country, but it is also part of Europe. Argentina is a South American country, it’s not in the northern hemisphere, but at the same time, inside South America it is an important country. So, I think this is a strange position to be in, especially regarding the field of theatre, it is not the same situation being in Latvia as it is being in Amsterdam, or being in Germany or Belgium that has a lot of weight in terms of money, but also in terms of production of discourses or where, where the real theatre is made. We also found that out and we always had this fantasy of how great it would be to create connections between peripheral countries without going through Brussels or Amsterdam, or the Goethe Institute, for example, how it usually happens. And our work The Last Night of the Deer is a little bit like that. It was produced in Riga and Kuopio and was very much self-organized with Jānis in his studio and residency space.

Can you tell a little bit more about the practical process of collaboration?

Jānis: I think we started last summer, like I was talking with Nahuel in spring, then we had a couple of sessions during the summer, but it was quite important to get into one room beforehand. The first big steps were during December, like last year, when we had that drive (that is also reflected in the show). Nahuel had this slow travel to Latvia, and we worked on the research – reading the essay, arriving at the concept or the storyline. And then we decided that we needed another meeting before we started to work on the premiere, so it was good we had a chance to work in a residency in Cassis for two weeks.

Nahuel: Yes, we were there for almost 10 days in Cassis in France. And, in between, we had more Zoom meetings, emails. In December it was more reading and then we started to write, in Cassis it was very much writing, and basically, then we had the structure. We were working at some moments in parallel, Jānis was writing, I was in the studio, working on the music that was coming together. And then in July, one year after the start, we met in Riga and we had a fun and intense regime of rehearsing almost every day. It was very good that we had the space, that we could rehearse in the location, so we could create it together with the space. And also, we had five days in Kuopio to finish the writing part. Jānis has more practice and skills in writing. But I was also writing and commenting, but I was more focused on the sound part, because it’s what I know more, but Jānis was also collaborating, advising me on songs and lyrics, so this was very collaborative.

Can you resume a little bit about what The Last Night of the Deer is about?

Jānis: I think if I trace back, then in December, we had this very important source from Eduardo Kohn’s anthropology book How Forests Think that is based on many years of field studies. At least for me, that was a different approach on how to think about the communication that is happening between species. For me, it was very complicated – imagining that you are a tree, for example, and that kind of thing. Because, honestly, I don’t think that really leads somewhere that much for me, or that I can really understand how a tree thinks or what it means to become a tree. When we were going through that work, our shared feeling was that our work should be able to communicate with the audience in a way that you don’t need to have a masters in biology or philosophy to connect. In that book, the important part is the transfer of knowledge through storytelling. And, we also tried to keep that. And then we organically arrived at the idea that we needed to have some kind of event, like traveling from Klaipeda to Riga through that snowstorm, and what happens while doing that. And, if you want, you can start to think that this kind of severe snowstorm is an outcome of climate change. These kinds of snowstorms will be happening more and more. But, we also didn’t want to say it openly or lecture someone that it is like that. No, if you want, you can go and think in that direction.

Nahuel: I think that book was also very important for me. It changed my way of understanding many things. It was a very nice experience to read this book together with Jānis. Of course, our understandings were not always the same because of having different backgrounds and ideas. But, most importantly, this book points out this possibility of communication, and at the same time – to the impossibility of communication. The impossibility of “A equals A”. That there is also a will to understand the total otherness, the other species. And, I think that that is also something that happened in ourselves – not the impossibility to understand, but the will to understand. And that’s why for me, this work is also about friendship. And that is something that we knew, but in a rehearsal, when it was already very close to the premiere, we had had an open rehearsal. In the material we had a moment where we had some kind of a conflict between the two of us. A conflict is a normal thing in theatre, but nobody who saw the run liked that moment. But then, Viesturs, Jānis’ cousin said, “But you are a co-pilot”. I will never forget that, for me, it was very important. To understand that there is no conflict in that sense… there is just a misunderstanding. But there is a will to find a solution together. And I think that is the beautiful thing about that piece about friendship, that it is about the potentiality of finding an opening to a future that had kind of looked like a dead end.

What would you say is the most specifically Latvian thing about Jānis? And what is the most Argentinian thing about Nahuel?

Nahuel: Oh, I don’t know (laughs).

Jānis: There’s one thing that we didn’t mention about what both places have in common. But, I think it has worked for us helping to connect to the book. The book author’s Eduardo Kohn’s research was also taking place in South America in Ecuador in a village where people believe in a forest’s spirits. And, I think in countries on the periphery, there is still this pathway of thinking and even sometimes even practices have not disappeared in their culture. I think for us this connection is on a different level, but it may help me to connect to someone who has a relationship with that kind of thing. But the most Argentinian thing about Nahuel… well, he has worked on tango shows. And also, he is the person who although he might be as tired as I am, or, he might be falling asleep, he will continue the conversation about this Argentinian band or folk musician, or tell me some story from his life, making me feel as if I was in Nahuel’s Argentinian culture podcast. The fact that he is valuing these things that are not even so thrilling, but there is a significant importance and truth about those things for him.

Nahuel: For me, Latvia is Jānis, in a way. He has been my way of meeting this city and country, a city that I now feel very close to. I have learned the city through his eyes. Also, I don’t know many other Latvian people, I have to be honest. And I think, from what I have experienced, for me Riga is a little bit like Montevideo, the capital city of Uruguay. There is this feeling of many layers of history coexisting and a certain melancholy in that coexistence. Buenos Aires (the capital of Argentina) is a very melancholic city, the real estate speculation is super hardcore there, and there are changes all the time, while in Riga, I think, it is a bit slower… But I have a feeling that Jānis is a little bit like that, in his person you can feel all these layers. It is not that he is living in the past, but it’s not all the time in the future, or not only in the present. There are these three times moving together. And I think that describes both Riga and Jānis.

Back